The Use of Naropin@ (ropivacaine HCI) in Interscalene Blockade for Shoulder Surgery |

|

|

Dr. John Wilson, MBChB,

Dr. John Wilson is Specialist Anaesthetist at Mercy Hospital, Dunedin and Visiting Consultant Anaesthetist in the Department of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, Dunedin Public Hospital, Dunedin, New Zealand. His clinical interests are regional anesthesia in orthopaedics, obstetrics and gynaecology, general and vascular surgery. |

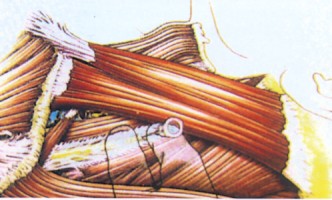

IntroductionInterscalene brachial plexus blockade for shoulder and upper-limb surgery is used to provide a pain-free surgical site for as long as possible intra- and post-operatively, and to avoid drugs with significant side-effects.1 Using Naropin® allows patients to recover quickly and mobilise as rapidly as possible with the minimum of nausea and discomfort.2 I use such blocks for open and arthroscopic procedures on the shoulder, e.g. acromioplasties, rotator cuff repairs, total shoulder replacements, debridement of labral and rotator cuff tears and anterior stabilisations. The use of concomitant sedation and general anaesthesia depends on the needs of individual patients, the surgeon and the type of operation. The aim is to provide anaesthesia that is well tolerated and relatively pleasant for the patient while providing optimal operating conditions for the surgeon, with the minimum of morbidity.1 In my experience, few patients opt for surgery under interscalene block alone - most opt for a technique involving general anaesthesia as well. AnatomyThe brachial plexus is formed principally from the anterior primary rami of the C5, C6, C7, C8 and T1 spinal nerves, and runs from the vertebral column between the clavicle and first rib, and enters the upper limb in the axilla before dividing into four main terminal branches - the median, radial, ulnar and musculocutaneous nerves.3 At the level of the 6th cervical vertebra and cricoid cartilage, the brachial plexus runs between the anterior and middle scalene muscles in a perivascular sheath, some distance from the subclavian artery and the pleural dome.1 The perivascular sheath, which contains the nerves and main blood vessels of the upper limb, allows local anaesthesia to spread up and down from the point of needle insertion.3 The extent of the spread of the anaesthetic agent depends on the location of the injection point and the volume, concentration and type of anaesthetic agent. The interscalene approach is relatively well tolerated and blocks the area around the shoulder more effectively than lower approaches, e.g. axillary block.3 |

TechniqueI use a brachial plexus anaesthesia set with a 22-gauge short bevelled regional anaesthesia needle attached to a syringe containing 20 ml of 10 mg/ml Naropin® (ropivacaine HCI) via small bore tubing so that injection does not disturb needle placement. In my experience, the addition of clonidine 150 p g usually prolongs the block. A nerve stimulator allows more accurate positioning of the block, especially in anatomically compromised patients. With experience, accurate placement using feel and landmarks is possible, with a low incidence of side-effects.4 As permanent nerve damage attributable to such a block is caused by direct needle trauma and/or painful intraneural injection, it is safer to carry out the block in an awake patient, although in experienced hands such damage is rare even in anaesthetised patients.1 The patient should be supine with their head rotated away from the block site. Supplemental oxygen should be administered. The groove between the anterior and middle scalene muscles is palpated behind the sternomastoid muscle, which is identified by asking the patient to raise their head. The needle is inserted at the level of the 6th cervical vertebra and cricoid cartilage into the interscalene groove perpendicularly to the skin, slightly downwards and backwards to avoid the spinal canal being penetrated. (See Figure 1 for needle placement). During slow advancement, paraesthesia of the hand and/or arm (twitching muscles with a nerve stimulator) shows correct placement.3 Paraesthesia/twitching of the shoulder girdle implies stimulation of the supraclavicular nerve and is equally successful in indicating correct placement of the block needle within the brachial plexus sheath.3,5

Once the needle is in place, the local anaesthetic is injected slowly in 5 ml aliquots interrupted by gentle aspiration to reduce the chance of intravascular injection. The onset of a successful block occurs within a few minutes, with maximum blockade taking 30-45 minutes.5 EffectsBrachial plexus block with Naropin® induces anaesthesia of the upper limb including the shoulder. As a result of the variability in anatomy and the inability to see exactly where the insertion needle is placed, the anaesthesia produced is quite variable. The anatomy in patients with short necks and patients who are obese makes producing an adequate block more difficult. A long-acting local anaesthetic agent such as Naropin® 10 mg/ml should be used, the relative safety of this drug allowing doses up to 300 mg.6 The duration of action is about 12 hours.7

|

Side-effectsAs the local anaesthetic is not confined within the perivascular sheath, some spread to other tissues occurs that may manifest as numbness of the face on the same side; variable paralysis of the vocal cord as a result of laryngeal nerve involvement (10-17% of patients),4,8 unequal pupils in 47-75% of patients (Horner's syndrome);8 and varying impairment of phrenic nerve function on the same side, causing relative immobility of the hemi-diaphragm.9,10 Systemic toxicity after interscalene blockade is uncommon and is usually the result of direct intravascular injection, with Naropin® providing advantages over bupivacaine.12 Injection into a dural cuff will result in a high spinal blockade with inevitable serious sequalae.12 The overall incidence of nerve injury is 0.1%, with the relationship between peripheral nerve damage and regional anaesthesia being controversial.13,14 A definitive cause of nerve damage is often difficult to establish as many possible causes are present in the peri-operative period.14 In my experience, Naropin® provides excellent analgesia using doses up to 300 mg, and has a reassuring safety profile.

References 1. Brown AR, Bigliani LU. Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy Review 1998, 6(3). 2. Bertini L, Tagariello V, Mancini S. Reg Anesth Pain Manage 1999, 24: 514-8. 3. Scott DB. Techniques of Regional Anaesthesia. Switzerland: Mediglobe, 1995. 4. Vester-Andersen T, Christiansen C, Hansen A et al. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1981; 25: 81-4. 5. Roch ii, Sharrock NE, Neudachin L. Anesth Analg 1992, 75: 386-8. 6. Naropin° approved product information. 7. Klein SM, Greengrass RA, Steele SM et al. Anesth Analg 1998, 87 1316-9. 8. Seltzer J. Anesth Analg 1977; 56: 585-6. 9. Urmey WF, McDonald M. Anesth Analg 1992; 74: 352-7. 10. Urmey WF, Talts KH, Sharrock N. Anesth Analg 1991, 72. 498-503. 11. Scott DB, Lee A, Fagan D et al. Anesth Analg 1989; 69: 563-9. 12. Casati A, Fanelli G, Aldegheri G Br J Anaesth 1999; 83:872-5. 13. Dhuner K. Anesthesiology 1948; 11. 289. 14. Parks BJ. Surgery 1973, 74. 348.

|

|

Produced and published by Please consult the approved Product Information before prescribing any drug mentioned in this publication. |